06.12.2018

What is governance?

The term ‘governance’ is used in many ways, but not always to mean the same thing. In the context of political control, the term includes the non-hierarchical forms of governance and, in contrast to government per se, implies a form of control designed to coordinate and link together political decision-making levels and stakeholders.

The term has since been transferred to the business environment and often crops up in the context of process and IT control. Here, governance consists of a defined organisational and operational structure that ensures that, for example, process design or changes to IT are aligned with the corporate strategy.

Does blockchain governance exist?

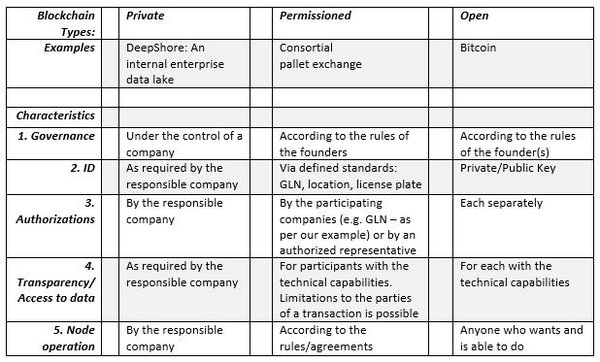

First of all, let us distinguish between the different types of blockchain solutions that companies can use:

- Private: This group primarily consists of the various ‘small’ solutions that have are used or predominantly used by one company

- Public: This category groups together the well-known, large, open cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Ether

- Permissioned: These are hybrid solutions that are particularly well-suited to multi-company solutions that are used by members of a business partner network. In this instance, access to the platform and rights to perform activities are controlled by rules

The following table shows the main features of the different blockchain types:

We can conclude from this that a private blockchain is controlled by normal IT governance, and that the issue of specific blockchain governance only applies to open and permissioned platforms. The governance of open blockchains is primarily determined by the founders. For example, Satoshi Nakamoto defined the vast majority of the rules that govern ‘his’ Bitcoin. The established governance process follows a defined set of verification rules and ultimately seeks to determine whether a proposed change will convince enough stakeholders so that it will be included in the reference implementation on github.com.

Further details on Bitcoin governance can be found in the following blog post: https://medium.com/@pierre_rochard/bitcoin-governance-37e86299470f

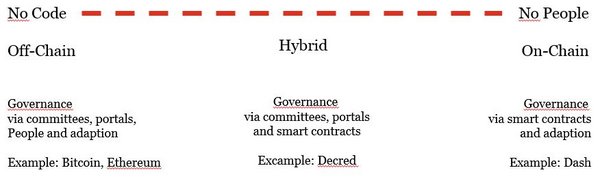

Studying existing open blockchain governance models enables us to recognise that different decision-making processes are used. Archetypically, a distinction can be made between ‘no code’ and ‘no people’. Both forms are based on the principle of adaption, i.e. whether a proposed change is actually installed by the majority of node operators.

Governance in the pallet exchange consortium – which approach is best?

A comparison between the different types of blockchain also reveals that the admission-restricted approach provides the largest scope for regulation. In the context of a permissioned blockchain solution used by a consortium business partner network, there remains the question of what exactly it is important to control. There is no best practice here, so we're treading new ground.

To start off, we shall define governance as a set of rules that govern our partnership. These regulations focus on what, who and how.

- WHAT is the subject of the regulation?

- WHO is involved, i.e. what are the roles and what are they responsible for?

- HOW will decisions be made, i.e. by committees, software or a combination of the two?

The governance system should be based on shared values. We agreed on the following:

- no dominance by a single player – as decentralised as possible

- open value-added chain – intellectual property (IP) is available to the consortium and can be exploited by its members

- the partnership and the distribution/exercise of power should be governed by rules

- collaboration between companies: the process and data standards for the consortium should be defined together and used

- a neutral platform for the exchange of load carriers. The solution is planned to be ‘open’; In other words, all members have access to the process, data and interface definitions. It can also be linked to a proprietary application solution

Who is responsible for forming the consortium?

One of the aims of governance is to establish a foundation of mutual trust, which allows companies to carry out their business processes – palette exchange in this instance – using the blockchain solution. In the case of our project, one essential requirement is that business partners are identifiable, because one partner gives another pallets in the hope of receiving either wood or money in return. This is an essential difference from the open cryptocurrency blockchain solutions, which allow everyone to see the transactions, but the business partner is hidden behind his public key.

In order to ensure the reliability, integrity and transparency of the pallet exchange solution, we need to consider more than just goal-oriented governance issues, such as changes to

- the data structure

- codes and

- technology.

Another critical area for us to look at is how to control our ecosystem. However, what does our ecosystem actually look like? We have defined the following stakeholders/roles:

- Decider: Similar to a temporary ‘board’ of the consortium, capable of making quick decisions

- Node operator: A company that operates a blockchain node within the pallet exchange platform

- Consortium member: A company that wants to be part of the consortium but doesn’t want to run a node

- Exchange service provider: A company that provides access to the platform as a service

- Exchange partner: Any company that is involved in the exchange process

- Service provider: software developer, infrastructure operator, etc.

The consortium itself comprises roles 1 to 4. A company is able to assume one or more roles. The company does not, however, need to be a member of the consortium to exchange pallets using the platform.

Our ecosystem will be controlled using the following types of contract:

- A consortium agreement, which outlines the rights and obligations of companies assuming roles 1, 2, 3 or 4

- Licence agreements, which control the relationship between an exchange service provider and its affiliated exchange partners, and

- Agreements that are issued to contracted service providers by the consortium or one of its members

It is recommended that the consortium be represented by a legal entity; failure to do so will automatically result in the creation of a private partnership (GbR). Alternative options include: a cooperative, an association, a GmbH (limited liability company) or a foundation. Several key factors should be considered when determining the appropriate form, e.g. the period for which the consortium will be formed, dealing with IP, tax and antitrust issues, voting rights, the possibility of expelling members of the consortium in case of breaches and, last but not least, the geographic scope.

What could be included in a consortium agreement?

In order to secure our proposed operational business partner network from a legal point of view, we have identified a number of topics that need to be defined:

- Preamble: purpose, goals, values

- Organisation: roles, responsibilities, voting rights, committees and audits (if applicable)

- Approval processes (subject of approval, no-code or no-people procedure) and the corresponding quorums and SLAs

- Incentives for specific roles

- Sanctions for specific offences

- IP rights and the free availability of process solutions and software for the consortium

- Data, data privacy and use of data

- Recognition of documented exchange transactions as legally binding

- Forming, recognising and dealing with deputies’ identities

- Dealing with non-compliant load carriers (quality discrepancies)

- Admission, withdrawal and expulsion of members of the consortium

- Contractual IT regulations: processing of business data, company liability issues

- Possible support processes and structures, together with associated SLAs

- Funding

This is an ongoing discussion involving a wide range of different opinions, which is why we are concluding this blog post with an incomplete list. It seems to reflect the fact that we are treading new ground here and encourages us to continue addressing these issues and reach solutions in the New Year.

Kommentare

Keine Kommentare